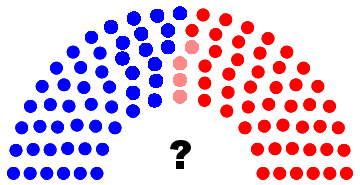

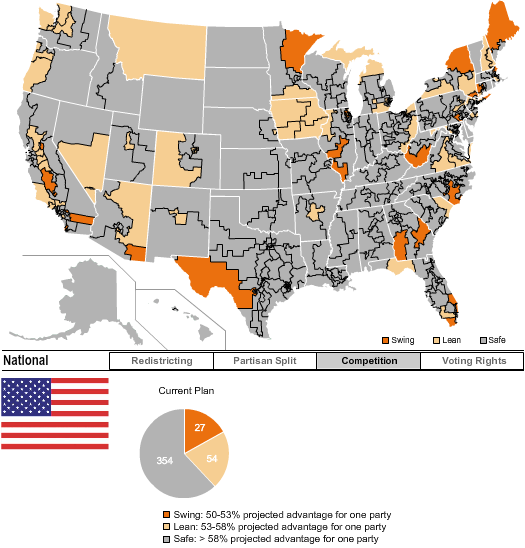

Dicussions of the Electoral College have lately been all over the news and social media, even more so than in a normal election year, in the wake of Donald Trump's lopsided victory. Though the election of Trump has been the rallying cry behind hundreds of thinkpieces and desperate petitions, there are far more oddities to the system than the possibility of winning a majority in the Electoral College while losing the popular vote, which has now happened four times in our history. Even in a "normal" election without an electoral split, the need for candidates to compete for electoral votes rather than an outright majority leads them to focus their time, money and attention on swing states, and modify their messaging and policy proposals to appeal to voters in those states. The process is also designed to give smaller states a mathematical advantage. The result is an election where some voters have far greater power than others, based on geography, to select the President.

None of this is news, but it is difficult to discuss the real extent of this power imbalance when we see it as an abstraction. Four years ago, I attempted to quantify these effects using a formula I developed, which I called the Vote Value Index. Today, I'm taking a look at the 2016 election using the same formula. I'll get into the mechanics of the formula later, but the upshot is that we're creating a list of values which we can use to compare states to each other, and easily find out how much power a state's voters have to influence the election, compared to voters in other states.

The Vote Value Index takes two factors into account that affects a voter's influence: the small-state advantage (which allows less populated states to punch above their weight in the Electoral College, and handicaps larger states), and the margin of victory (because a vote is more influential in a "swing state" with a small margin). It is important to note that we are not looking for the probability that a single voter will cast the "magic vote" that will tip the election. We are simply measuring how much power each voter has to move the needle in either direction. It's also important to note that the Vote Value Index is dynamic, and will change from one election to the next, based on the closeness of each contest as well as changes in population.

The states are listed below in order of their voters' individual power. The Vote Value Index is shown using the state with the least powerful voters (in this year's case, California) as a baseline. California's VVI is set to 1.00. All other states' VVI represents a multiple of the value of a California vote. In other words, a state with a VVI of 10.0 means that a voter in that state has ten times more influence than a voter in California. The Percent Value vs. Popular Vote is a comparison of a voter's influence under the current system to the same voter's influence if we simply used the nationwide popular vote to select the President. This is determined by dividing the state's VVI by the average VVI of all states. (Note: this data is based on unofficial returns, and may not include provisional ballots that are still being counted. The information is accurate as of November 14.)

| Ranking | State | Vote Value Index | Percent value vs.

popular vote | Rank in 2012 | 2012 value vs.

popular vote |

| 1 | NH | 247.39 | 1,826.95% | 2 | 310.59% |

| 2 | MI | 105.83 | 781.54% | 30 | 55.85% |

| 3 | WI | 36.62 | 270.43% | 21 | 92.40% |

| 4 | ME | 33.07 | 244.22% | 18 | 107.38% |

| 5 | MN | 26.17 | 193.26% | 19 | 96.77% |

| 6 | NV | 24.63 | 181.89% | 6 | 189.95% |

| 7 | PA | 24.43 | 180.41% | 20 | 94.63% |

| 8 | FL | 20.29 | 149.84% | 1 | 598.73% |

| 9 | AK | 14.14 | 104.42% | 3 | 275.09% |

| 10 | RI | 10.53 | 77.76% | 17 | 109.68% |

| 11 | DE | 10.23 | 75.55% | 13 | 123.16% |

| 12 | NM | 8.81 | 65.06% | 12 | 133.48% |

| 13 | VT | 8.65 | 63.88% | 16 | 114.38% |

| 14 | AZ | 8.58 | 63.36% | 23 | 78.36% |

| 15 | CO | 7.72 | 57.01% | 14 | 122.76% |

| 16 | NC | 6.96 | 51.40% | 4 | 252.23% |

| 17 | WY | 6.37 | 47.04% | 10 | 137.20% |

| 18 | GA | 6.26 | 46.23% | 22 | 81.58% |

| 19 | VA | 5.62 | 41.50% | 9 | 143.85% |

| 20 | SD | 4.73 | 34.93% | 8 | 148.16% |

| 21 | ND | 4.65 | 34.34% | 7 | 179.60% |

| 22 | IA | 4.50 | 33.23% | 11 | 134.54% |

| 23 | MT | 4.24 | 31.31% | 15 | 122.64% |

| 24 | CT | 3.40 | 25.11% | 34 | 46.30% |

| 25 | NE | 3.24 | 23.93% | 25 | 72.37% |

| 26 | TX | 3.23 | 23.85% | 38 | 39.24% |

| 27 | OR | 3.16 | 23.34% | 29 | 57.01% |

| 28 | OH | 3.10 | 22.89% | 5 | 250.88% |

| 29 | UT | 3.05 | 22.52% | 49 | 24.96% |

| 30 | HI | 2.94 | 21.71% | 37 | 43.14% |

| 31 | SC | 2.60 | 19.20% | 26 | 71.41% |

| 32 | NJ | 2.59 | 19.13% | 41 | 37.21% |

| 33 | MS | 2.55 | 18.83% | 24 | 73.93% |

| 34 | KS | 2.51 | 18.54% | 36 | 44.09% |

| 35 | DC | 2.43 | 17.95% | 31 | 53.10% |

| 36 | ID | 2.34 | 17.28% | 33 | 46.57% |

| 37 | WA | 1.99 | 14.70% | 35 | 45.44% |

| 38 | IL | 1.94 | 14.33% | 42 | 33.25% |

| 39 | KY | 1.90 | 14.03% | 44 | 29.73% |

| 40 | WV | 1.81 | 13.37% | 32 | 49.50% |

| 41 | AR | 1.81 | 13.37% | 40 | 37.73% |

| 42 | LA | 1.76 | 13.00% | 39 | 37.94% |

| 43 | IN | 1.68 | 12.41% | 28 | 60.08% |

| 44 | MO | 1.61 | 11.89% | 27 | 60.53% |

| 45 | MD | 1.42 | 10.49% | 47 | 25.48% |

| 46 | AL | 1.40 | 10.34% | 43 | 32.66% |

| 47 | NY | 1.32 | 9.75% | 51 | 19.84% |

| 48 | TN | 1.20 | 8.86% | 45 | 29.71% |

| 49 | MA | 1.12 | 8.27% | 48 | 25.46% |

| 50 | OK | 1.08 | 7.98% | 50 | 22.04% |

| 51 | CA | 1.00 | 7.38% | 46 | 27.41% |

Before the election, a friend of mine from high school learned that his absentee ballot had been lost in the mail. It was too close to election day to sort it out and get a replacement ballot, so he bought a last-minute plane ticket back to New Hampshire so that he could vote in person. It now seems that his beyond-the-call-of-duty trip home was quite meaningful, even if his candidate didn't win the Presidency. The state of New Hampshire had the highest VVI in the nation this year, and its voters had 247 times more influence over the election than voters in California.

Comparing the 2016 VVI with 2012 presents a bit of a challenge. I did not include the 2012 VVI in the above chart (though you can view them here), because directly comparing the VVI from two different elections is not very useful due to the changing baseline. However, looking at the top VVI for each year can show us how a very close election can widen the power imbalance. In 2012, the top VVI was Florida's 30.18 (compared to New York's 1.00, which was the 2012 baseline). This means that in 2012, the most powerful voter in the country had about 30 times more influence than the least powerful voter; in 2016, the most powerful had 247 times more than the least. This extreme imbalance comes mostly from how close the 2016 election was. In 2012, Florida was the only state with a margin of victory smaller than 1%, and only four states had margins smaller than 5%. In 2016, there were three states with margins under 1%, and a whopping eleven states were within 5%. This gave swing-state voters much greater power to influence the Electoral College, because it would have taken fewer voters to flip their state.

We can also compare the elections by the difference in a vote's value under the current system vs. a popular vote system. A percentage of more than 100% means that a state's voters have an advantage, gaining more influence through the Electoral College than they would have without it. States with less than 100% have diminished vote values due to the EC system. In 2012, there were 18 states with comparitive values over 100%; these states' voters punched above their weight, and everyone else was hamstrung. This year, only nine states held this advantage. And as this additional power narrowed into a smaller number of states this year, the magnitude of the disparity increased. The most advantaged voters in 2012 had about six times the power that they would have had under a national popular vote, while the most disadvantaged had about 20%, one-fifth, of what they would have in a popular-vote contest. This difference is nothing compared to 2016. This year, New Hampshire's voters had more than 18 times as much power as they would without the EC, while Californians had a miniscule 7% of their power under the alternative system.

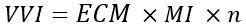

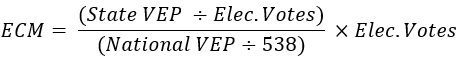

I'm going to get into the nuts and bolts of the VVI formula now, so those who aren't interested in the math can feel free to skip to the end. On the other hand, if you'd like to follow along or see how your own state's VVI was calculated, you can view the full data set as a Google spreadsheet. The formula itself has three parts, shown here:

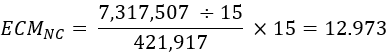

These represent an Electoral College modifier (ECM), a Margin Index (MI), and a constant (n) which sets the baseline. The first part, ECM, reflects a state's advantage or disadvantage based on their voting-eligible population (VEP) and the number of electoral votes. This represents the "small-state advantage."

The voting-eligible population includes all of the state's residents who are U.S. citizens, at least 18 years old, and not disenfranchised due to a felony conviction or other reason. I used the 2016 estimates of VEP from the United States Elections Project. I use VEP, rather than total population or registered voters, because this is the true total number of people who could potentially cast a ballot. Ineligible residents, even though they affect the allocation of electoral votes, cannot affect the election outcome; and there is no effective difference between an eligible but unregistered person and a registered voter who doesn't show up to cast a ballot.

On average, there are 421,917 eligible voters for each electoral vote in the U.S., but because of the way the EVs are allocated, some states have more or less voters for each electoral vote. Wyoming has a population of 431,011 and three electoral votes, meaning there are only 143,670 Wyomingites per EV, giving them a far greater than average influence on the Electoral College. The formula assigns them an ECM of 8.81. Any state with an ECM higher than their number of electoral votes is a beneficiary of the small-state advantage.

Using my own home state, North Carolina, as an example, we find an ECM of 12.973, smaller than our 15 electoral votes. This electoral handicap befits our status as the 9th most populous state in the Union.

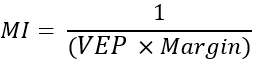

The next part of the formula is the Margin Index. This gives a boost to voters in states with close elections, particularly "swing states."

The Margin Index multiplies the VEP times the margin and then inverts it. The denominator represents the number of votes that it would take for the minority candidate to achieve a majority. The numerator of 1 represents the individual voter.

Naturally, this results in a very small number; we are measuring the influence of one voter to change the majority in an election with a large number of other voters. The MI may seem small in absolute terms, but it will be orders of magnitude higher in a close election than in a state with a runaway winner. In a moment, we'll shift these numbers into a range that we can more easily work with.

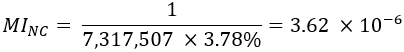

Revisiting North Carolina, we find that the MI looks like this:

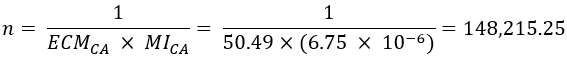

The final part of the formula is a constant. The purpose of this constant is simply to apply a baseline for comparing the states. As I mentioned earlier, we want to set the state with the least powerful voters to have a VVI of 1.00. By multiplying the ECM and MI that we have so far, we find that California's presidential votes were the least influential in 2016. We get our constant by inverting California's preliminary numbers.

Finally, we multiply the ECM, MI, and the constant for all of the states to get the final VVI.

North Carolina's VVI is just under 7, which tells me that my vote is seven times more influential there than if I lived in California. My state dropped sharply in the rankings this year, from #4 to #16, mostly due to the change in margin; we were one of the closest states in 2012, but our margin nearly doubled in 2016. The change in value against a popular vote system was drastic, too. The Electoral College advantaged North Carolinians in 2012, making our vote roughly 2.5 times more powerful. In 2016, the EC instead handicapped us by about half.

Clearly, I am in favor of abolishing the Electoral College, regardless of where my own state stands in the rankings from year to year. You won't see me signing any petitions to try and convince 37 faithless electors to change this year's results, though. We knew the rules of this election when we started it, and for better or for worse, Donald Trump will be our next President. This doesn't mean that we need to maintain this antiquated system forever, though, and I strongly support the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, which could be enacted through state legislatures without amending the Constitution.

Of course, there are a number of arguments that are often made in favor of the Electoral College system. I find most of these arguments, however, to be weak.

One argument is that the Electoral College gives rural states a voice that they wouldn't have under a popular vote, which would benefit large cities. The problem with this argument is that cities are going to have an advantage no matter what system we use. Candidates will never have much incentive to hold a campaign event in Spivey's Corner, NC (pop. 448), even in a swing state, because their resources are finite and there aren't many votes to be had there. However, they do have an incentive to focus on swing-state cities like Cleveland, Raleigh and Orlando, and largely ignore safe-state cities like Dallas, Boston and Salt Lake City. Even moderately-sized cities in swing states, such as Wilmington, NC, get plenty of attention from candidates. Under a popular vote, candidates would be just as likely to visit Billings, MT, which is roughly the same size as Wilmington and would allow more rural voters to have their voices heard. Of course, the campaign is one thing and the election is another; but under a popular vote, the rural voter in Montana would have more than three times the influence that they had in 2016, and would not be taking a back seat to voters in New Hampshire and other states.

Some also argue that the Electoral College places a check on the "tyranny of the majority" and could prevent a dictator from taking office. I find this argument to be preposterous. The people who are chosen to be electors in the modern era are mostly insiders and loyalists, chosen by state parties to reward them for their service to the party. Occasionally one or two might change their vote, but these "faithless electors" have never influenced the outcome of an election. Furthermore, many states have laws that could penalize or even invalidate a faithless elector's vote. A majority of electors would only risk their positions and the nation's outrage if it was very clear that a "tyrant" was looming. The electors aren't clairvoyant; they can only judge a candidate on their statements and record, the same as the rest of us. It would be audacious and premature to predict that Donald Trump will become a literal tyrant, but if the things he's said on the campaign trail aren't enough to sway the electors, what would be?

Finally, there is the idea that the Electoral College is what the founders intended, so who are we to mess with it? Naturally, I have a great deal of respect for the founders of this nation. They were visionaries who created a modern democratic system, unheard of in their time, and defended it from the greatest powers of their contemporary world. They built a Constitution that has endured for 240 years, and served as a model for democracies throughout the world. They started a wave in which democracy and freedom are now the global norm, rather than the exception. But we in America have a tendency to treat the founders as almost Biblical figures. Even great men have flaws, and so do their works. The founders were, after all, politicians. They squabbled just as much as today's politicians; they were just better at looking at the bigger picture and finding a compromise. They were just as good at kicking cans down the road, too. Some of the founders opposed slavery, and saw no place for it in a society founded on the idea that all men are created equal. Unfortunately, they didn't have enough like-minded colleagues, and they needed the southern states to buy in to keep the newborn nation from falling apart. Of course, by delaying the issue, the nation nearly fell apart anyway, four score and seven years later.

We've learned a lot in 240 years, and we value different things. In many ways, the founders prioritized the concerns of the states over the concerns of the people living in them. In the first election, only one state, Virginia, even held a popular ballot for President. The rest of the electors were chosen by state legislatures, leaving the people out of the process entirely. We didn't hold a popular vote in every state until after the Civil War.

The founders knew that they wouldn't get everything right on the first go. In fact, they called a mulligan on the original Articles of Confederation only eight years after it was ratified, and started over with a Constitution that would work better. We've made many changes since then to improve the way the nation operates. All of this follows my favorite line of the Constitution, from the Preamble: "to form a more perfect Union." Not a perfect Union; true perfection is impossible, and we can't know the needs of future Americans any more than the founders could have known ours. But a more perfect Union, one that forever strives to improve itself, never satisfied to stay ossified when there is a better way.