On October 22, Presidential candidate Donald Trump announced a new set of policy proposals that he hoped to accomplish in his first 100 days if elected. One of the proposals was to push a Constitutional amendment that would enact term limits for members of Congress. This idea, unlike many of Trump's controversial proposals, is one with a history of broad support among voters on both sides of the political divide. It appeals to people who feel, justifiably, that Congress is not working, and that career politicians are focused more on preserving their jobs than solving the problems facing the country. However, there are better ways to address this problem than imposing term limits; and furthermore, term-limiting members of Congress could do more harm than good.

It is easy to be cynical about Congress, especially when the last few sessions have been the least productive in history, and Congressional approval ratings are at all-time lows. However, I believe that most people who run for office do so, at least initially, out of a genuine desire to serve the public and make the nation a better place. It is true that many elected officials end up cycling out of politics and into lucrative positions in business, finance, and lobbying; however, this is not often their goal when they first decide to run. Anyone who has the skill set needed to serve in Congress can undoubtedly find a shorter and less painful path to making that kind of money. After all, serving in Congress is utterly thankless; it requires relocation or constant travel from home; the pay is not that great compared to others requiring similar skills; there's no job security; and you can expect your name to be dragged through the mud on television during each election.

In spite of this, people run for office because they feel strongly about the issues they represent, and wish to advocate for their constituents. However, no matter how idealistic they may be when they are sworn in on Day One, they find themselves on Day Two already running for reelection, and end up spending half of their time fundraising instead of working on the business of state. In order to maintain their position, eke out some influence and political space to push their agenda, and get assigned to a committee where they can sponsor some legislation, they need the support of their party's senior leadership; and that means, among other things, more fundraising - for your colleagues as well as for yourself. The more you hope to accomplish, the more time you spend on the phone with donors and bundlers, as well as lobbyists who want some consideration in return.

This is often an argument used in favor of term limits, but that won't solve the problem. If you were to limit members of the House of Representatives to, say, three terms, you would still have around two-thirds of the members running for reelection every two years. The senior members, in their third term and ineligible for reelection, would likely still spend a lot of their time campaigning for their chosen successors, as well as their party's junior members, and often for a new office for themselves elsewhere.

Trump did not mention how many terms he thinks is the proper limit, nor have most term-limit advocates, prefering to leave that decision to be negotiated in bill-drafting. The last proposal to gain traction in Congress, put forth by Rep. Bill McCollum in 1995, would limit Representatives to six terms and Senators to two terms - essentially, limiting both houses to 12 years in total. This bill did not get much support among the strongest term-limit advocates, mostly because the 12-year limit was seen as too long to make much of a difference. Most members of Congress do not serve for that long anyway; in 2015, the average length of service was 8.8 years for Representatives and 9.7 years for Senators.

What if we went whole-hog and limited members to a single term? This would solve the reelection conundrum, as no member of Congress would be eligible to run again. However, this would have a severe impact on the running of Congress. With the entire House of Representatives filled with 435 incoming freshman, there would be zero continuity of government, no momentum on issues not resolved in the previous session, and each incoming Congress would have to reinvent the wheel in terms of how they conduct business. The seniority system would be busted at last; but as imperfect as that system is, at least it is a system. Without it, each session would spend precious months determining who the leadership would be and how committees would be assigned. (Some people may even advocate for the abolition of committees, giving each member equal power to push legislation on any subject. As egalitarian as that sounds, it would result in utter chaos, given the amount of business that needs to be covered in the complex modern era.)

Most importantly, though, it would mean that 435 complete strangers would be put into a room and asked to work together to solve the most important and difficult problems in the country. Politics is a profession that is based on personal relationships. Nobody can go it alone; in order to get a bill passed, you have to negotiate and compromise, and come up with something that can get the support of more than half of Congress. That can only come by forming professional relationships with fellow members, both within your own party and across the aisle, knowing where they stand, what they want and need, and how you can convince them to support your position. It also takes the expertise of people who spend years researching and advocating for the issues they care about.

A single-term limit, of course, is an extreme case, and beyond what any serious person is advocating for. As I described earlier, however, nothing less will solve the problem that we're trying to address. If we want to get members of Congress off of the phones and back to work, our best option is to get serious about campaign finance reform, and change the lobbying rules.

Another important problem with term limits is that it can harm accountability. Voters, ideally, judge their legislators on their record, and ultimately, the voters will decide whether they deserve to be reelected. A long-serving member of Congress does not get to that point without broad support within their own district. Frequent elections are how we ensure that our Representatives are truly representing their constituents. A term-limited member, however, has no accountability to those who voted them into power, because they will never face those voters again. On the other hand, voters may be denied the right to keep a popular Representative, who has done good work for them and advocated well for the issues they care about, due to term limits.

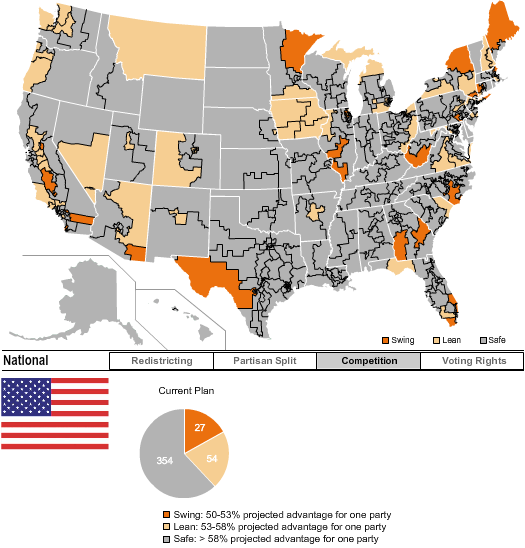

Of course, if accountability were that easy, the approval rating of Congress would be higher than 18%. Voting out an unproductive or intransigent member, unfortunately, is more difficult than it ought to be. There has always been an incumbency advantage, but that advantage is made much stronger due to gerrymandering. By drawing district lines to favor one party over the other, and packing most of the opposing party's voters into the smallest possible number of districts, all of a state's districts are made uncompetitive. The practice is rampant, used by both parties, and has become all the more egregious in recent years. As a result, the voter advocacy organization FairVote has estimated that only 27 of the nation's 435 House seats are truly competitive this year.

Source: FairVote

Not only does this protect incumbents from being ousted, it also encourages members of Congress to be more extreme and less willing to compromise. With the general election largely a formality in many districts, an incumbent's party primary is the only real contest they will face. Thus, their party's base of primary voters is the only constituency they will be accountable to. This makes members unwilling to compromise on important issues and more likely to focus on partisan fringe issues, lest they be replaced by someone else who will. They become deaf to the concerns of their district's citizenry as a whole.

Term limits won't solve these issues, either. A party-line representative who is barred from reelection can just be replaced by another. The only way to make Congress truly accountable is to reform our redistricting process. By shifting the authority to draw district lines away from state legislatures, and into independent, bipartisan commissions, legislators would no longer be able to choose their own voters when it should be the other way around. In an ideal world, we would adopt FairVote's Fair Representation Act, forming independently-drawn, multi-member competitive districts, with Representatives selected by ranked choice voting.

Congressional term limits are simply another populist-minded, sound-bite-oriented proposal that sounds good on the surface. In practice, it doesn't address the problem it's meant to solve, and distracts from the true reforms that we need.