Tuesday's elections in the Virginia House of Delegates cannot be described as anything other than a wave. The Republican Party, previously one seat shy of a two-thirds supermajority, saw their advantage nearly eliminated by Democratic challengers. The total popular vote over all districts, which favored Republicans in 2015 by a 26% margin, swung to a 9% Democratic margin in 2017.

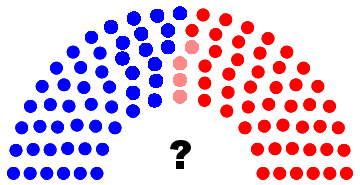

As of November 12, the election results suggest a Republican lead in 51 of the 100 districts. In four of those districts, the Republican lead is less than 1%, triggering a recount. Those recounts, as well as any provisional ballots yet to be counted, will determine which party controls the Virginia House. In one of those districts, the Republican candidate currently leads by only thirteen votes.

How likely is it that the recounts will change the results? Data from the nonpartisan electoral-reform organization FairVote suggests that the odds of a recount flipping an election's outcome is roughly three in twenty-seven. This is based on a study of statewide, not district, elections between 2000 and 2015, so it is not a perfect analogy, but it is close enough for a decent guesstimate. I ran a simulation that assumes that each recount has a 3/27 (about 11%) chance of resulting in a Democratic pickup - with the exception of the 94th district, the one with the 13-vote margin. Since that one is so close, I doubled the odds to 6/27. The actual odds may be higher, since the number of provisional ballots might significantly exceed the margin.

In order for Republicans to hold the majority, they need to retain their leads in all four districts that are being recounted. If Democrats are able to flip at least two of these districts, their party takes the majority. If only one of the recounts results in a Democratic victor, the House will be deadlocked at a 50-50 tie.

Based on the odds described above, I projected that Republicans hold a roughly 55% chance of retaining their majority by winning all four of the recounts. Democrats have about a 9% chance of gaining enough seats to take the majority. The remaining 36% of simulations resulted in a deadlocked House. You can view and re-run my simulation here, if you like.

What's most shocking about these results is that despite the fact that 53% of Virginia's voters chose Democrats, leading Republican voters by a 9% margin, Democrats only won 49% of the seats solidly. Even in recounts, they have less than a one-in-ten chance of gaining the majority, and just over a one-in-three chance of a tie, in spite of what would seem to be the clear choice of the people of Virginia.

Part of this can be explained by the number of uncontested races. In the 2015 election, when Republicans won 61% of the statewide popular vote and 66 of the 100 seats, there were a whopping 71 out of 100 contests where only one of the two major parties fielded a candidate. Of those 71 candidates who stood unopposed (or opposed only by independent, third-party or write-in candidates), 44 were Republicans and 27 were Democrats. This year, the Democrats really stepped up their candidate-recruitment game. Roughly the same number of Democrats (28) stood unopposed by Republicans in 2017, but only 12 Republicans sailed to victory without a Democratic challenger.

In fact, the advantage in uncontested races explains much of the popular-vote margin in both 2015 and 2017. Even with their depressing effects on voter turnout, these races allow one party to run up the vote tally unanswered. So in 2015, when 44 Republicans ran unopposed - nearly half the chamber - of course they won the statewide vote by a large margin. Democrats swung that advantage in their favor in 2017 by fielding more candidates without Republican efforts to do the same, so they won the popular vote this year. In fact, if you count only districts in which both a Republican and a Democrat were on the ballot this year, the Republicans won 54% of the total votes.

This would seem to challenge the narrative of a Democratic wave, but there is another factor in play. That factor is, of course, gerrymandering. Given what we've learned about the contested races, it may not seem that gerrymandering had much of an effect here. After all, Republicans won 54% of the vote in contested races, but are barely hanging on to a majority of seats and may lose it, how can we say that the districts are drawn in a way that advantages Republicans?

For one thing, in those 60 contested districts where Republicans got 54% of the vote, they hold a lead in 39 of the races (65%), showing they still hold an advantageous position based on how those districts are drawn. But more importantly, the uncontested districts are a feature, not a bug, of Virginia's gerrymandered maps. To understand this, we should discuss how gerrymandering is done. It involves two steps, often called "packing" and "cracking." The party in power "packs" as many opposition voters as they can into a few districts, giving the minority party a handful of safe seats that they will win by very wide margins. The rest of the opposition voters are "cracked" - spread as thinly as possible across the remaining districts, often drawing lines through the middle of neighborhoods in order to split them up and dilute their votes. Thus, the party drawing the maps gives themselves a larger number of safe seats than the opposition - though they will usually win those seats by smaller margins than the packed districts.

This is part of why the Democrats' candidate recruitment effort was so successful. Many of the districts where Democrats did not field a challenger in 2015 but did in 2017 are "cracked" districts, where they are at just enough of a disadvantage that they can't win in a normal year - but they could pose a serious challenge in a wave year. On the other hand, the districts where a Democrat ran unopposed are "packed" districts, where the Democratic advantage is so strong, any Republican challenger would just be throwing campaign dollars down a well. But from the Republican perspective, that's just fine. These super-safe Democratic seats give the GOP that many more opportunities to build their majorities elsewhere, and by not fielding a challenger in these packed districts, the party saves resources that they can focus on the rest of the state.

Virginia's voter turnout this year, at 47%, is the highest it has seen in a state legislative election in twenty years. Despite this, in the districts that were not contested by both major parties, 20% fewer voters came to the polls on average than in contested districts. Voters in these districts can be forgiven for believing that their vote wouldn't matter much in this election. Safely-drawn districts, particularly those featuring uncontested races, lead to reduced engagement by voters. Imagine what turnout may have been if every seat had been challenged by both major parties. Better yet, imagine if the districts weren't drawn to protect incumbents and give one party or the other a baked-in political advantage - if more districts were actually competitive.

Regardless of these challenges, the Virginia election stands as an example of how much voting really matters. Even in the face of a gerrymandered map, the people of Virginia were able to cut a Republican supermajority down to a statistical tie. And even if the GOP holds onto all 51 seats after the recounts, their slim majority will make it more difficult to pass legislation without Democratic support - and to gerrymander the next round of maps in a few years, depending on the 2019 results. But the greatest example of the power of a single vote is Virginia's 94th district. A race separated by a mere thirteen votes may determine the balance of power in the entire House of Delegates. It could have been yourself and a dozen friends; few enough people to fit in a single room, deciding the future of a state. Under the right circumstances, that is the power of the ballot.